Volcanism in the Caribbean

- Home

- Volcanism in the Caribbean

Volcanism in the Caribbean

The Caribbean islands stretch in an arc linking North America to South America. Many of these islands were formed by ancient underwater volcanic activity. Eruptions gave rise to volcanic islands such as Guadeloupe, Montserrat, Dominica, and Saint Vincent, where “new” volcanoes can still be found today. Officially, there are 21 active volcanoes in the Caribbean. All of them are stratovolcanoes, except for the caldera-type volcano of Saint Lucia and the underwater volcano known as “Kick ’em Jenny.” Although often dormant for many years, most islands host at least one volcano—from Saba down to Grenada—with the notable exception of Dominica, which is home to nine.

The Caribbean islands are also part of what is known as the “Ring of Fire,” the zone that contains the largest concentration of volcanoes in the world, located around the Pacific Ocean. This is because most of today’s subduction zones are found around the Pacific.

What is a volcano ?

First of all, we need to understand the difference between a so-called “active” and “extinct” volcano.

By definition, an active volcano is generally one that goes through phases of activity alternating with periods of dormancy, which can last for hundreds of years. Some volcanoes remain active for hundreds of thousands or even millions of years, while others are born and, after only a few days of activity, fall permanently asleep. It is impossible to know in advance whether a volcano will stay active or not. For this reason, by convention, a volcano is considered active if it has erupted at least once in the past 10,000 years.

An extinct volcano, on the other hand, is one for which the time since its last eruption is far greater than the average length of its past dormant periods. However, this does not mean that it can never awaken again.

(example : Mont ST Helen, USA, Mount Saint Helens | Location, Eruption, Map, & Facts | Britannica).

The terms

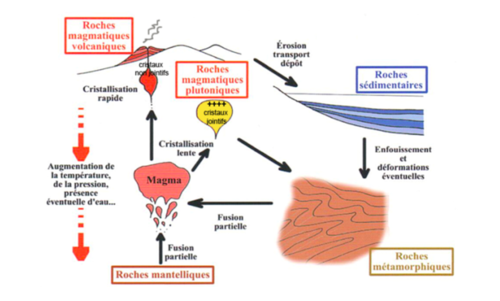

Volcanism encompasses all the natural phenomena related to volcanic activity, particularly volcanic eruptions, as well as the presence of magma within the Earth. Volcanology is the science that studies how volcanoes work and the related phenomena, including magmatism.

Magmatism is an expression of the transfer of the Earth’s internal heat. It therefore contributes to the overall cooling of the planet.

Magma and lava

Lava and magma both originate from molten rock.

Magma is the source of the lava released at the surface. Near the surface, the drop in pressure causes the magma to degas, losing its volatile components (dissolved gases). Its chemical composition then changes: lava generally contains less iron and magnesium, and more calcium, sodium, or potassium.

The chemical composition of erupted lava is therefore different from that of magma.

In addition, once lava flows at the surface, some of its elements also tend to oxidize on contact with air—for example, sulfur.

Eruption

We have seen the difference between magma and lava, but now it is important to understand the process that allows these liquids to rise. In depth, magma behaves like an interstitial liquid—that is, it lies between two layers—within a solid porous matrix.

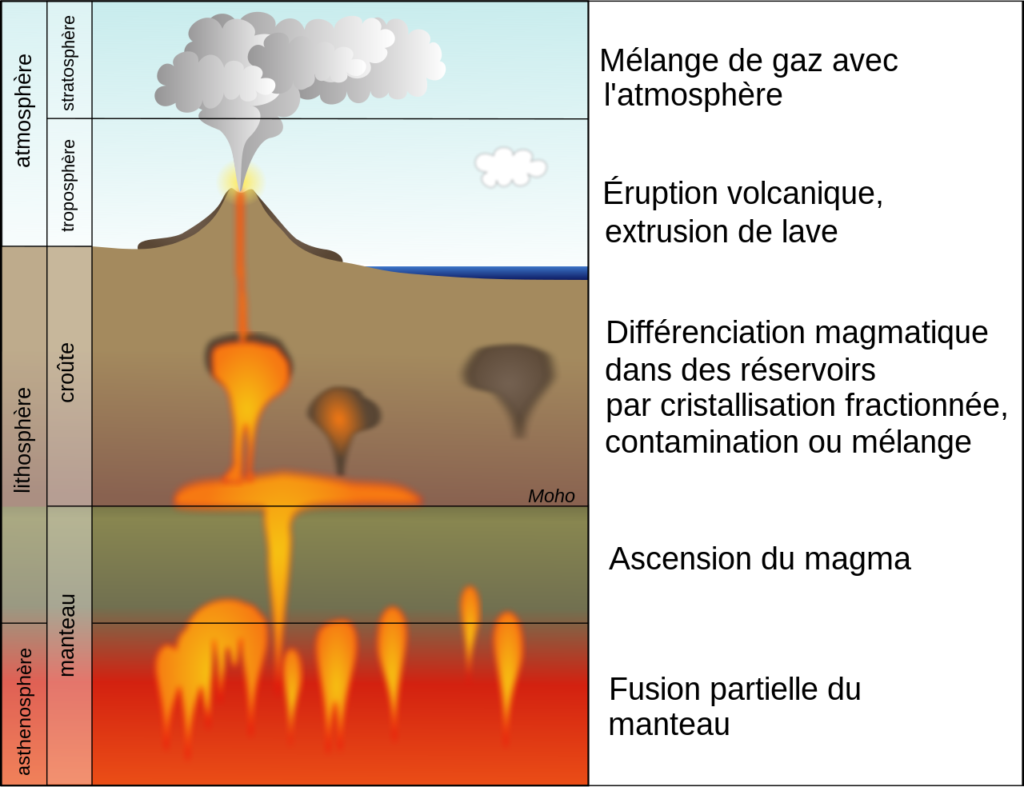

Magma, being less dense than the surrounding rocks, is driven upward by buoyant force (Archimedes’ principle). As it rises, it fractures the rocks through dikes or diapirs. This ascent is facilitated in fractured zones and may stop at various depths, forming plutons, or reach the surface during volcanic eruptions. Sometimes, magma accumulates in magma chambers before being released. The ascent rate depends on its viscosity, ranging from about 1 m/s for basaltic magma to as little as 10⁻⁴ m/s for more viscous magmas such as rhyolites.

As magma rises, it causes a drop in pressure, leading to the partial exsolution of dissolved gases. This results in bubble formation, which reduces the magma’s density and increases its volume. This expansion raises the pressure within the reservoir, fracturing the surrounding rocks. This process triggers earthquakes and ground uplift, facilitating the eruption. The gases migrate toward the surface, accelerating the magma’s ascent and making the eruption inevitable beyond a certain point.

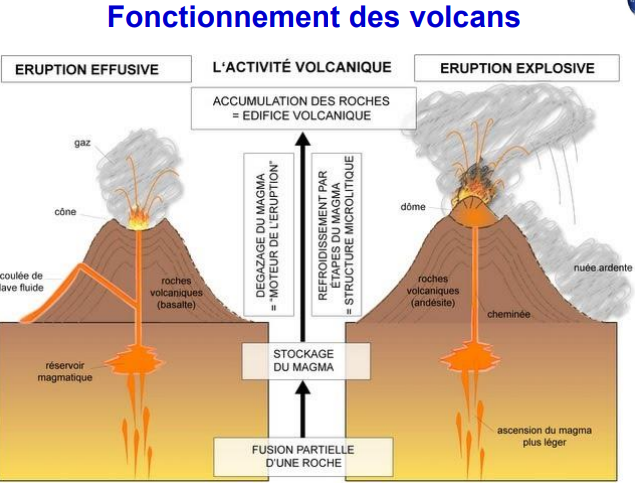

Magma fragmentation occurs when gas bubbles form a continuous phase, shattering the magma into fragments carried by a gas jet. If fragmentation does not occur, the eruption takes the form of a lava flow, resulting in what is called an effusive eruption.

In the case of fragmentation, the velocity of the lava fragment jet can reach 50 to 200 m/s, close to the speed of sound, and remains independent of the magma’s viscosity. The flow exits at a pressure higher than that of the atmosphere, generating shock waves (explosions), resulting in what is known as an explosive eruption.

Types of Eruptions and Volcanoes in the World and in the Caribbean Two main types:

- Effusive (lava) eruptions: These are Hawaiian-type volcanoes with “fluid” lava flows. They are commonly referred to as red volcanoes.

- Explosive eruptions, of various types, but mostly gray volcanoes (little or no lava flow, producing gray clouds):

- Strombolian volcano (gray and sometimes red)

- Vulcanian volcano (gray)

- Plinian volcano (gray)

- Pelean volcano (gray)

- Submarine volcano

Volcanic risk is a serious concern for our territories. Understanding how this natural force works is therefore essential.

While we generally imagine volcanoes producing red, fluid lava like Hawaii, volcanoes in the Caribbean are different! They produce thick, viscous lava. Because of its viscosity, this lava doesn’t travel far from the vent. It accumulates and forms gigantic (lava) domes, which explode during an eruption.

These volcanoes typically cause pyroclastic flows, or pyroclastic flows. This phenomenon is a deadly volcanic hazard. It is a rapid avalanche of hot ash and rock fragments in a gas cloud whose temperature probably exceeds 600 degrees. They appear to us as a large column of debris projected into the atmosphere and they descend the valleys at speeds that can exceed 160 km/h, destroying everything in their path. They are also very difficult to predict, therefore, to survive, it is necessary to evacuate the threatened areas as soon as an alert is given.

To pyroclastic flows, the explosion causes projectiles and ash fall. Ash destroys vegetation, contaminates water, and can cause breathing difficulties. It is therefore best to stay indoors (in a safe area) or wear a suitable mask. Driving during ash fall is not recommended, as visibility is poor. In rainy weather, driving becomes even more dangerous due to slippery roads.

Moreover, these eruptions cause large blocks of rock to move. Like cannonballs, they usually land less than a kilometer from the event. To survive, you must stay out of their range and trajectory.

Here is where to consult the maps of volcanic risk zones in the Caribbean:

https://uwiseismic.com/downloads/volcanic-hazard-atlas-of-the-lesser-antilles/

Lahars, another consequence of the eruption, are also dangerous because they are also difficult to predict. They are mudflows laden with water and burning sediment that cascade down the side of the volcano. We have seen them regularly in Martinique; the last one was in 2018.

Although many events are difficult to predict, volcanic islands have observatories on their territory that, using various techniques, monitor the occurrence of volcanic earthquakes, the swelling or deflation of the volcano using satellite views and many other tools.

Here's where to consult the monthly bulletins from the Guadeloupe Volcanological Observatory and see the Soufrière in near real time:

http://www.ipgp.fr/fr/ovsg/observatoire-volcanologique-sismologique-de-guadeloupe

Also, in addition to this preventive information, it is important to always be prepared. To do this, you must:

- find out which organization is responsible for preventing volcanic risks in your area,

- know your island’s emergency plan,

- know where to take shelter and get information in case of evacuation.

Are you ready ?

Volcanic eruptions can occur in a short period of time, so evacuation orders should always be followed immediately. Everyone has a role to play; the first step is knowing where to find accurate information. You’ll need to identify your island’s disaster management organization and know which local newspapers to turn to in the event of a crisis (they should be sourced from the relevant authorities).

The second step is to learn about the volcanic hazard zone in your area. You need to know if you live, go to school, or work in this area and what hazards are likely to affect you. You need to know the routes to avoid and the best routes to take when evacuating a hazardous area.

It’s also important to know your island’s volcanic alert system and levels (colors). You should also know your island’s emergency plan in case of a volcanic eruption.

The third step is to equip yourself with an emergency kit, which may include a battery-powered radio, a flashlight, ash masks, medications, water filters, disinfection pills, and other essential supplies.

The fourth and final step is to communicate your family plan (how you operate) in the event of a volcanic disaster to each member of your family. You should also talk to your relatives and friends who are outside the danger zone to arrange (if necessary) temporary accommodation (outside the danger zone).

- Video summary of instructions in case of eruption: Se préparer face à une éruption volcanique | Catastrophe naturelle

- Action plan in the event of an eruption in Guadeloupe (ORSEC plan):https://www.guadeloupe.gouv.fr/Politiques-publiques/Risques-naturels-technologiques-et-sanitaires/Les-risques-telluriques-en-Guadeloupe/Activite-volcanique-de-la-Soufriere-de-Guadeloupe-et-sismicite-regionale/Le-plan-ORSEC-Volcan

- Information in case of eruption in Dominica: http://odm.gov.dm/resources (en anglais)